Think You’ve Cine It All?

25 Mar, 2019 | Elin Donnelly

The Arts and History & Politics

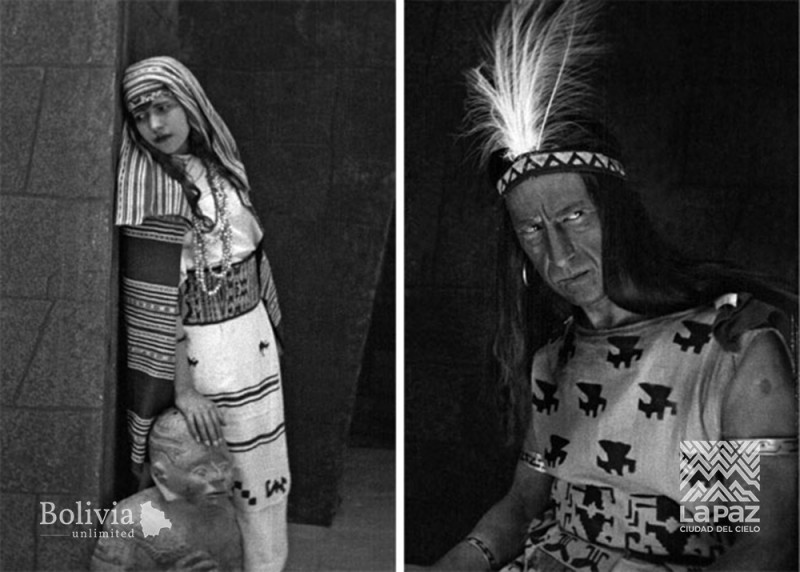

Vuelve Sebastiana. 1953

Photos: Courtesy of Fundación Cinemateca Boliviana

The Bolivian film industry is small, but it’s a vital part of the country’s culture

Back in the horse-drawn-carriage days when the nation was less than a century into its independence, the first-ever motion picture shown in Bolivia was aired to the public within the darkened halls of the Teatro Municipal. The year was 1897, and that moment marked the beginning of Bolivia’s lengthy and diverse history of cinema. Returning now to 2019, on 21 March the nation will celebrate its 13th annual Día del Cine Boliviano, a day of national cinematic pride dedicated to the Bolivian filmmakers, directors, producers and actors of the past 122 years. With the approach of this significant day in the Bolivian cultural calendar, we take a look back at the nation’s motion picture past.

Bolivia’s cinematic career begins in the Silent Era, in the year 1904 with the first-ever Bolivian-made motion picture, Retrato de personajes históricos y de la actualidad (Portrait of Historic and Current Characters), a documentary portraying the country’s ongoing transitions of power. Today, the Silent Era is only somewhat understood, as approximately 70 percent of the world’s silent films have been lost. In Latin America, however, this figure is considerably higher, and as a result Bolivia has little today to show for this period. Bolivia’s sole surviving silent film, a motion picture that has very much come to define this period in Latin American filmmaking, is Wara Wara (1930), directed by the prominent Bolivian musician and director José María Velasco Maidana. Its nitrate negatives were not discovered until shortly after the director’s death in 1989, and it wasn’t until 2010, after two decades of restoration, that the film was viewed for the first time since its original release. The 16th-century Romeo-and-Juliet/Pocahontas narrative tells of an indigenous Aymara community that is massacred by Spanish conquistadors, forcing the few survivors, including the young princess Wara Wara, to flee. After being rescued from the grips of two Spanish soldiers, she delves into a romance with her knight in shining armour, Tristan de la Vega. The rest of the film follows the triumph of their inter-ethnic romance over the prejudices of their communities as they finally live happily ever after.

Claudio Sanchez, a Bolivian film critic with over 30 years’ experience, is currently head of programming, broadcasting and exhibition at La Paz’s Cinemateca. Following the passing of Bolivia’s Ley de Cine y Arte Audiovisual in 2018, promulgated to promote national film production and preserve its contributions to culture, Sanchez was tasked with preserving the country’s cinematic heritage through the upkeep of its national film archive. Wara Wara is a film of particular interest to Sanchez, both because of its significance to Bolivia’s film history and its status as an emblematic record of Bolivia’s indigenous heritage. Speaking with Bolivian Express, Sanchez explained how important Wara Wara is for indigenous representation within the country’s history, as it ‘showcases the Inca communities within the film as a dominant group. [In Wara Wara] we don’t see just any indigenous character, we see an Inca princess – not somebody inferior to the Spaniards, but a strong character.’

For the time in which he made it, Velasco Maidana presented a rather progressive outlook on the treatment of Bolivia’s indigenous peoples. Through his work he was able to denounce their suffering, not only in the 16th century but also in the 20th, by creating developed and accurate representations of indigenous characters.

Many years later, in 1952, as revolution hit Bolivia, no single aspect of popular culture was left untouched, least of all that of cinema. As Brazil developed its Cinema Novo and Argentina its Tercer Cine, Bolivia sought also to create a new kind of cinema with which to define its national identity. The subsequent trend in Bolivian cinema has since been characterised by a shift towards grappling with political debate relating to issues such as underdevelopment and economic hardship, particularly within Bolivia’s indigenous communities. Defined also by its deviation from the ever-popular Hollywood style of film production, this trend in Bolivian cinema reflected an attempt to create a genre of film made for the people by the people, by filming on location rather than in studios with nonprofessional actors and cheap equipment. Indicative of this time and of the artistic battle that besieged the industry is documentary film director Jorge Ruiz’s 1953 work ¡Vuelve Sebastiana! (Come Back Sebastiana!). As this was a period of Bolivian history in which government censorship was commonplace, the authorities attempted to prevent the film from being submitted to Uruguay’s Servicio Oficial de Difusión, Radiotelevisión y Espectáculos film festival in the year of its release, characterising it as ‘a film about “Indians” [that] could not possibly represent Bolivia in a foreign country’s film festival.’ Against all odds, however, ¡Vuelve Sebastiana! was eventually smuggled into the festival and awarded first place in the festival’s ethnographic category. As a result of its success, the film is now of huge anthropological value in South America due its progressive representation of indigenous traditions, customs and rituals.

Bolivia’s 1952 revolution left no single aspect of popular culture untouched, least of all that of cinema.

Another huge name in the Bolivian film world is that of Jorge Sanjinés. Born in 1936, Sanjinés’ work is defined by its political agenda and revolutionary aesthetic, and he’s considered a game-changer and hugely prominent figure in the cinematic world, with his work as a film director and screenwriter continuing to be felt today. His standout motion picture, encapsulating this era of revolution, is Yawar Mallku (Blood of the Condor), a film Claudio Sanchez described as ‘one of the most important films of the 20th century.’ This 1969 production portrays a narrative of indigenous Andean women being secretly sterilised by a Peace Corps–styled American group called Cuerpo del Progreso. Based on accounts of real experiences, this film ignited public outrage which in turn led to the Bolivian government questioning the Peace Corps’s intentions in the country and their eventual expulsion from Bolivia in 1971. Demonstrated by the film’s stark ability to enact such change in the country, Yawar Mallku rightly deserves its reputation as a Latin American classic for illustrating the power popular culture has in influencing politics and international affairs.

In the following decade, filmmakers began to move away from Sanjinés’ vision as a wave of dictatorships arrived in South America. Directors began experimenting with a lighter form of social realism and attempted to concoct a new kind of film through different methods of production. This genre is characterised by a more traditional and commercial narrative style, contrasting with Sanjinés’ love of flashbacks and nonlinear narrative structures. At the time, this branch of film was known as ‘Possible Cinema’ and tended to focus more on urban social portraits. Chuquiago (La Paz, 1977), by Antonio Eguino, and Mi Socio (My Friend, 1982), by Paolo Agazzi, are typical of this style with their descriptions of contrasting Bolivian cities and regions and playful adaptations of class stereotypes. This transition eventually paved the way for a new generation of Bolivian filmmakers who enjoyed experimenting with genres in an allegorical exploration of social realism.

In more recent decades, Bolivian cinema has been completely transformed with the advent of digital media. What was once a mammoth task, that of filming feature-length movies in daring locations with unwieldy equipment – a task that Bolivian film critic Pedro Susz once likened to ‘building the Concorde aeroplane in a car garage’ – was suddenly made accessible to the masses. Digital editing made production cheaper, and subsequently over a dozen feature-length films have been produced each year since 2010, a stark contrast to the two-films-a-year average seen previously. The variety of genres appearing in popular Bolivian film at this point also began to expand as filmmakers continued to move away from Sanjinés’ iconic cinema of denunciation. Films employing the already popular social-realism mode prevailed whilst broadening their range of social commentaries to include those of problems surrounding immigration, drug trafficking, corruption and gang violence. Secondly, ‘auteur cinema’ made its way to Bolivia as films featuring a clear artistic signature began to form the emergence of another popular cinematic genre within the country. And finally, moving away from the 1960s film-era mission to offer an alternative to the Hollywood style, a more commercial realm of film production eventually began to emerge, with Bolivian filmmakers trying their luck with comedy, action and even horror.

Despite the benefits of this expansion in Bolivian cinema and artistic expression, there are a select few who would argue that in some ways the industry has suffered as a result of this increased saturation. Commenting on this belief, Claudio Sanchez said, ‘As a consequence of digital intervention, [Bolivian] cinema has lost its place in the international arena as well as losing popularity locally because most filmmakers are solely interested in is producing these ‘genre’ movies: crime films, horror, action. All they are doing, however, is competing with similar Hollywood films, which are always better made. A [Bolivian] horror movie will never triumph over a Hollywood equivalent.’ In this alternative take on the trajectory of Bolivian cinema, Sanchez believes that in order for it to prevail and retain its international name, it must focus on that which it does well: social commentary made by Bolivians for Bolivians.

Bolivian film has woven itself into the fabric of Bolivia’s past by both creating and recording the nation’s history.

But upon closer inspection, however, there are modern Bolivian productions that do just this. Eduardo López’s Inalmama (2010), for example, is an 85-minute motion picture bringing Bolivian cinema full circle as it takes on the form of filmmaking first popularised by Retrato de Personajes Históricos y de Actualidad in 1904. The film, according to López, depicts a ‘political, visual and musical essay of the coca leaf and cocaine in the cultures of Bolivia.’ This documentary challenges the criminalisation of a product that exists not only as the key ingredient in cocaine, but more readily as a source of vital and legal income for many Andean communities.

Looking back, it’s clear how fundamental cinema’s role is in documenting Bolivia’s modern history. It is not just an account of the past 122 years of Bolivian cinema, but an account of the past 122 years of Bolivia itself. Bolivian film has woven itself into the fabric of Bolivia’s past by both creating and recording the nation’s history. In the words of Claudio Sanchez, ‘[Bolivian cinema] is a cinema that keeps on questioning its reality, and that, in each one of its films, reflects a history of all that has occurred in our country. I feel it is important for foreigners to see that Bolivian cinema is constantly reacting to its context. You cannot separate one from the other. When you watch a Bolivian film, you have to locate it in its moment, in that context.’

In the past year alone, a spectacular array of films have hit the screens of Bolivia and countries further afield, such as Loayza’s Averno (Hell), a fantasy story which plays with Bolivia’s attitudes to life and death; Richter’s El Río (The River), a story of young love amidst a culture of machismo; and, most recently, Erick Cortés Álvarez’s El Duende (The Goblin), a psychological horror thriller. With the arrival of these new filmmakers and new films, there is no doubt that Bolivian cinema is on the cusp of many more exciting cinematic possibilities. In Bolivia today, filmmaking is no longer as complex as building a jet in a shed, and so hopefully this modernisation of storytelling will prevail and expand for many a year to come.

Chuquiago

Chuquiago

Mi Socio 1982

Wara Wara 1930

Ukamau 1966

Instituto Cinematográfico Boliviano 1953

Inal Mama 2010