The Nikkei of Bolivia

21 Sep, 2017 | Nick Ferris

Photo: Nick Ferris

Seeking utopia halfway across the world

Deep in the breadbasket country of eastern Bolivia, around the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, exists something rather remarkable. In the centre of a broad and dusty town lies a low pagoda-like structure fronted by a large wooden gate and dark-green walls, and topped by golden Japanese characters. ‘That building is a kominka, the traditional house of Okinawa,’ says Nobutoshin Sato, the secretary general of the Bolivian-Japanese Nikkei association and my guide to the two Bolivian-Japanese colonies of Okinawa and San Juan de Yapacani. This particular structure in Okinawa, quintessentially Japanese but nevertheless happily lying along the main road of a typically Bolivian town, represents the symbiotic existence Japanese settlers have come to find in eastern Bolivia.

Immigrants first came from Japan to Bolivia in the late 19th century to take advantage of the rubber boom in the departments of Pando and Beni. Those enterprising people came on their own to a wild and undeveloped country. Their descendants have long since been absorbed into the wider Bolivian population, for the most part leaving no trace of their heritage but their surnames.

The Japanese in the colonies of Okinawa and San Juan came in the aftermath of World War Two, escaping their defeated homeland alongside hundreds of thousands of other emigrants who sought a new life South America. The government of Bolivia granted 50 hectares of land to Japanese families in return for their manpower. Okinawa was named after the American-occupied Japanese island from which the settlers came, while San Juan was named after the land in which they settled. In the first ten years of immigration beginning in the early 1950s, 3,200 Japanese people settled in Okinawa and 1,600 in San Juan. Today, around 800 live in each. Both colonies have found great wealth through their agricultural endeavours: Okinawa is famed for its production of grains and cash crops like rice, wheat and soya; while the smaller colony of San Juan produces more specialist items like citrus fruits, macadamia nuts and eggs – currently 700,000 eggs a day.

Latin America has historically been perceived as a land of exoticism and utopia, a new world for migrants to begin a fresh and idealised existence. Both towns have a strange sense of a closed, idealised community inherent to the endeavour of founding a colony. They have Japanese-run hospitals and schools, Japanese graveyards and restaurants, and access to Japanese TV. Yet a visit to San Juan’s museum with Masayuki Hibino, the 78-year-old president of the Bolivian-Japanese Nikkei association, revealed the settlement had a far from ideal beginning.

Hibino is an Issei, or first-generation immigrant, who took the two-month ferry journey to South America in 1957, aged 18. ‘My father was a specialist at selling and repairing cameras but his business was failing,’ he tells me. ‘There was only a 30% employment rate, everyone was struggling to get by.’ Faced with no apparent future, his family was drawn to Japanese state propaganda offering a new life in Bolivia. ‘My father had two houses in the city,’ Hibino says. ‘He sold them for ¥600,000 [or $800 per house] in order to pay for transport to South America. We were promised land, access to a main road, a school and other amenities.’

The reality of their arrival, says Hibino, was very different. ‘We arrived in Corumba [a city in southern Brazil] and were sent across South America in trains designed for cattle. When we reached the land designated for us,’ he recalls, ‘there was nothing there, only jungle. We had to transport all our crops through the jungle with horses. We built the first school by hand with hojas de motacú,’ he says, ‘it was a choza.’

Returning to Japan was also not an option.‘The boats were coming from Japan,’ Hibino explains, ‘we weren’t going the other way. Plus, if we wanted to go back we would need to pay $3,000 each. At that point, we were only making $14 a month.’

The situation was the same, if not worse, in Okinawa, where the first settlement was met with an epidemic of a variant of the hantavirus in which 15 settlers died. There were times of drought, times of flooding. They moved the settlement twice before settling for good.

‘We were promised land, access to a main road, a school and other amenities.’

–Masayuki Hibino

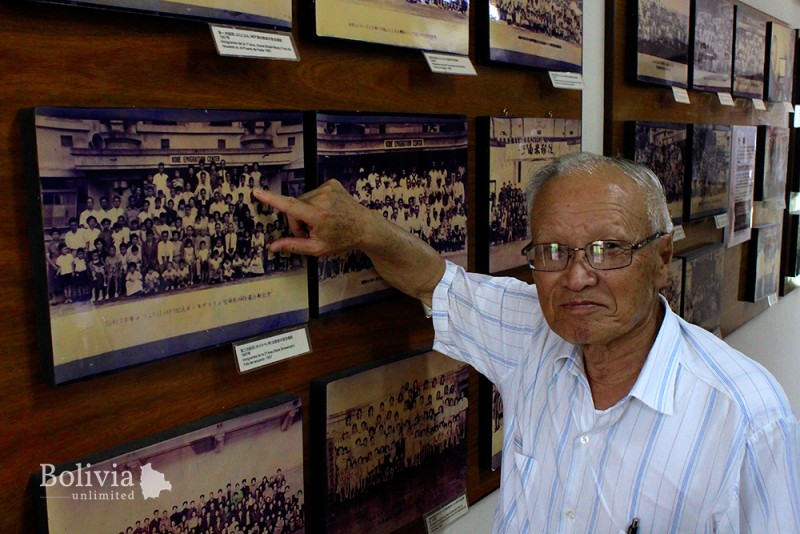

It was very affecting to hear the elderly Hibino’s story, to have him eagerly show me photos of his family at the port in Kobe prior to their departure and of his community’s struggles in the early days. He proudly showed the kimonos, a samurai sword and other artifacts the settlers had brought with them. He even demonstrated how the old, pedal-operated picadora de arroz worked. Hibino, who has seen the rise of his community, was understandably nostalgic about times past.

Meeting Satoshi Higa Taira, the secretary of the Japanese organisation in Okinawa, was a different story. Higa is a Nisei, or second-generation immigrant. He has a Bolivian wife, speaks fluent Spanish with a camba accent and identifies more as Bolivian than Japanese. Perhaps it is among this more settled generation that the Bolivian-Japanese utopia has been found.

‘We are born here, we only know this way of life,’ he tells me. ‘We see the competitiveness of countries like the USA and Japan. There is so much pressure there and everything is the same.’ Higa is among many Japanese known as the Dekasegi (‘the returned’), who went back to Japan in the 1980s to take advantage of the booming bubble economy. He then came back to Bolivia, preferring the more relaxed and less repetitive Bolivian way of life, to a modern, fast-paced Japan, where returning emigrants are not always welcome.

Unlike the early days that Hibino described, current-day Bolivian-Japanese have more land, mechanised farming techniques and more money and are at the forefront of an ever-growing consumer market that has opened across the country. ‘There is a stability now,’ says Higa.

The Japanese colonists have also forged a hybrid sense of identity, taking advantage of favoured aspects of Japanese and Bolivian cultures. Local shops, for example, sell Japanese products that are unavailable elsewhere. According to one Nisei in San Juan, when the younger generations come home to the colonies from university in Santa Cruz, ‘they eat, eat and eat! Our Japanese food is something that will never change.’

Higa also stresses the importance of a Japanese-style education. ‘We want our children to have the same education and attitude as they would have in Japan,’ he says. ‘This attitude is what is most important.’ The hard-working, resourceful ‘attitude’ of the Japanese people has of course made them successful all around the world. Yet it was also evident, in the way I travelled around with Nobutoshin Sato, jumping from minibus to minibus and sharing street food along the way, that for modern Bolivian-Japanese this ‘attitude’ translates into a thorough engagement with everyday Bolivian life and society.

The modern colonists are also very generous with their cultural heritage. Locals are invited to all events at the cultural centres. ‘We really want to include everyone in our traditions and activities,’ insists Higa. The Japanese schools welcome Bolivian and Japanese children, teaching in Spanish in the morning and Japanese in the afternoon.

So, is this utopia? A utopia is a place defined as the pinnacle of aspirations and dreams. It seems human nature dictates that such a state of entire fulfillment will never truly exist for our species. Just like the dream-like propaganda that Hibino’s family fell for 60 years ago in Japan, the reality of life in the colonies will never be utopian. The sense of contentment evident in the Nisei and their descendents masks the incredible toil and effort that they invest in their communities to make them successful. And with success comes a handful of other problems, like Bolivian farmers migrating to the area to sell products under the name of ‘Okinawa’ or ‘San Juan’ and take advantage of their reputation for quality.

The Japanese colonists have forged a hybrid sense of identity, taking advantage of favoured aspects of Japanese and Bolivian cultures.

The prosperity of the colonies cannot be taken for granted. But as Higa says, if the modern residents of San Juan and Okinawa sustain the qualities and attitudes of their founders, they will surely continue to prosper in the years to come.