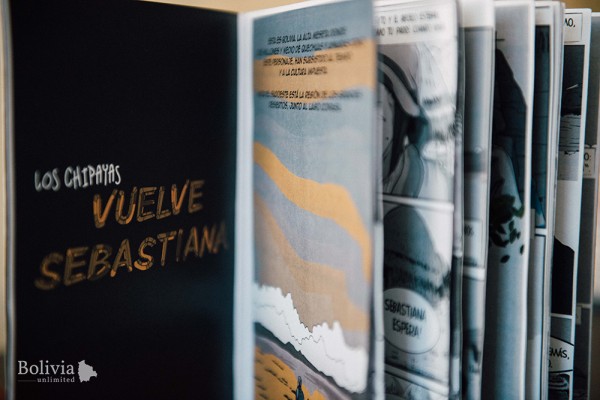

Sebastiana Returns

23 Aug, 2017 | Raquel Diaz

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

A classic of Bolivian cinema receives new life as a graphic novel

Flipping through the pages of one of the two copies in existence of ¡Vuelve Sebastiana! Los Chipayas, a graphic novel based on Bolivia’s first internationally acclaimed film of the same name, one sees Bolivia’s simultaneous gravitation toward celebrating tradition and looking beyond its borders toward a globalised world. The tale of the fading Chipaya indigenous population is rendered through anime-like art, meant to appeal to younger, contemporary audiences.

The late Bolivian director Jorge Ruiz filmed Vuelve Sebastiana in 1953. Despite being filmed over 60 years ago, the issues shown in the film are still relevant today.

‘We are in an age in which cultures are almost disappearing,’ says Guillermo Ruiz, the director’s son. ‘Documents like [the graphic novel] are all we have left. They revalue and rescue culture.’ Like his father, Ruiz is also a filmmaker and makes documentaries. ‘The book and film go hand in hand,’ he continues, adding that the screenplay has been adapted for the graphic novel, word for word. ‘Children can view them for assignments and learn about other lifestyles,’ he says.

The graphic novel’s artist, Juan Ariel Camino Aparicio, adds, ‘We want to use the book as a method of teaching kids, as a larger part of modern Bolivian education...By rescuing these ancient cultures, we learn about our identity. We are forgetting who we are as Bolivians.’

Vuelve Sebastiana is the story of a Chipaya girl, Sebastiana, who ventures away from her impoverished tribe and runs into an Aymara boy who is brandishing lots of food. Her grandfather sets out to find her. Once he does, he recounts the glory days of their tribe, days of celebration and fertility, to persuade her to come back. This story resonates with contemporary audiences as it calls for a return to one’s roots. For most Bolivians, that means returning to these ancient cultures.

Vuelve Sebastiana is more than a love story between the indigenous youths. It is an important anthropological work that echoes traditions of oral and visual storytelling. Since the Chipayas were not familiar with cameras at the time of filming, the filmmakers first spent time with the tribe and involved themselves with their quotidian life. Slowly, they started taking out their cameras without filming, and eventually they started recording. According to Ruiz, the Chipayas were unaware that they were being filmed, resulting in a heightened authenticity that is uncommon in the field of anthropology.

It won the James Smithson Bicentennial Medal in 2006, due to its ‘contributions to visual anthropology’ and earned Jorge Ruiz the title of ‘father of indigenous cinema’. Apart from the medal bestowed by the Smithsonian Institution, the film has obtained many other awards and was one of the first Bolivian films to rise to international fame.

According to Ruiz, it is crucial to preserve Chipaya culture due to its rich history. The Chipayas are the oldest peoples of the Andes, descendents of the ancient Chullpa tribe. When Jorge Ruiz filmed Vuelve Sebastiana, there were only about 1,000 Chipaya people alive in the region. To this day, the population is still low, at about 2,000 people. Ruiz attributes the decline of this culture to migration and poverty.

The poverty and struggles conveyed in the film are still relevant to Bolivian politics regarding indigenous people. The issues it presents ring truer than ever. ‘Under the government of Evo Morales, there is more healthcare and education for indigenous people, but not enough,’ Ruiz says. Years after the film came out, ‘Sebastiana’s husband died from a lack of medical attention in his community,’ Ruiz says. ‘He died from appendicitis, a disease that is very easy to cure.’ According to the Bolivian newspaper La Razón, Sebastiana herself has not been able to escape poverty, despite her starring role in the film.

Aparicio, the graphic novel artist, plans to visit La Paz this October to promote the work, hoping to find a publisher. He also has ambitions for future projects adapting Jorge Ruiz’s cult films into more graphic novels. Mina Alaska (1968) is part of the series of pending projects aiming to rescue and preserve Bolivian culture and history.

Like Sebastiana, it seems many Bolivians have powerful reasons to return to their cultural roots. ‘The film still has an impact, even on children,’ Ruiz says. ‘We screened it at some schools and the children were touched. The teachers were also happy to see it because it shows culture reflected through the eyes of a little girl.’